(Poland Street Wharf, the hottest place I have been to in New Orleans.)

Sweat will remind me of New Orleans. Twenty years from now, I will step out of my

air-conditioned car and into the hot summer heat in a supermarket parking lot. Little beads of sweat will appear instantly on the end of my nose and in the small of my back as I lock my door. It will make dark spots under my arm pits and soak my socks. I will pause as I reach for a shopping cart in the cart caral and the overwhelming heat takes me back to the hottest experience in my entire life.

I have been to a genuine desert in the middle of Colorado at the base of the Rocky

Mountains. It was a small park, probably nine square miles, a deposit for sand that was funneled through a crack between two massive mountains.

In the glossy informationpamphlet, the Park Service reminds visitors to wear thick-soled tennis shoes or hiking boots. No flip-flops or any other open-toed shoes, it warns, as direct contact with the scorchingsands could result in third degree burns. I went on a three hour hike over the sand duneswith no water and came out both sunburned and windburned. With my recent experiencewith heat in New Orleans, I now look back on that experience with pleasure. “There was such a nice breeze. Not like here,” I tell my parents over the phone wistfully.

I come home every day with evidence that all the sweat from my entire day is still

sitting on my skin in thick disgusting layers. If I really want to gross myself out, I can take my fingernails and drag them over my skin and be rewarded with sweat in a solid form. Often I will ride my bike for hours on end, exploring the city and its tiny cracks and crevices. I come back home and there are white salt stains on the shins of my pants, small deposits of salt embedded in fabric. I think they are disgusting. I remember my grandfather telling me that cows and deers are attracted to salt deposits and will lick them for nutrients. If that’s so, then they would probably love to lick my pants at the end of the day. There would no doubt be lots of delicious nutrients for them.

Sometimes my legs get so sweaty that I have to roll up my pants, take my thumb

and pointerfinger in the shape of a “C”, and squeegee the sweat off of my shins.

Then I flick it onto the hot blacktop. It evaporates in a matter of seconds. I have counted. Substantial drops of sweat will sit on the pavement, and BAM! three seconds later they totally vanish into the atmosphere.

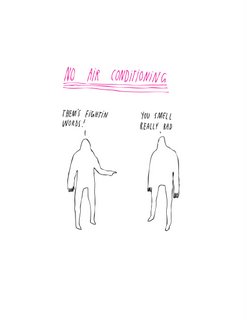

New Orleans is definitely the hottest place I have ever been to. It is consistently hot. Now it is the very end of October, and while it might be freezing in Kentucky, I can still expect a sweaty back if I go biking with a backpack on. It is very hard for me to picture a New Orleans before air-conditioning was invented. There would probably be a lot of cranky, smelly people walking around. That is how I picture it.

There are two things I have noticed through intensive research and extensive

personal experience that may have helped people deal with the suffocating heat and humidity: one is the shade produced by large trees, and the second is the shotgun house.

The shotgun house type migrated to the Southern United States from Haiti and

Africa by way of the slave trade. To the Haitians, this tall, skinny, extended structure was the building type used for meeting halls (“togun”, meaning place of assembly, possibly being reprocessed into “shotgun”). New Orleans was the first place that this housing type waswidely used, first seen here definitively in 1832. It has nice cooling qualities. In my shotgun house on Poland Avenue, we can open all the windows and enjoy nice breezes as they carry the sounds of our neighbor Vanessa yelling at her four yelping chihuahuas over Celine Dion. On special occasions, we can hear the sound of Vanessa yelling at her mom. This is also usually accompanied by

Celine Dion. When all the windows are open, the house becomes a large shed roof with

no walls. I like this very much.

I also like the shade under trees too. It becomes a nice place to go to when

Vanessa’s whole family comes to visit.

Sometimes I like to sit at Markey Park, the park a block up from studio that we are

designing this semester. The shade is perfect there at certain times of the day, but you have to be careful where you step because lots of dogs like to use the park. The users of the

park have brought generic plastic chairs and left them under the trees. There is really no

other place to sit except for the ground.

I find these chairs to be very beautiful. They are white resin chairs under all the coats of paint people have applied. Over time these coats of paint have been chipped or worn off from sitting and constant use, which makes them more interesting. The people in the park can simply move them from sunlight to shade whenever they feel like it, as opposed to fixed benches, which cannot be moved and are not responsive to the lighting conditions in the park. Some people resent resin chairs. They find them tacky and tasteless. I always try to find the best in chairs. I like them all. The resin chairs have a noble lineage- Eero Saarinen dreamed of producing a chair that was a “structural total”. “I look forward to the day when the plastic industry has advanced to the point where the chair will be one material,” he once said. These chairs are Saarinen’s dream come true.

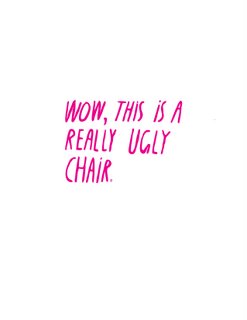

My favorite chair is a smaller resin chair that I sit in whenever I

get coffee and there is good weather.

Your first impression might be, “Wow, this is a really ugly chair,” and you would be right. It is a really ugly chair. Usually when I see chairs this ugly they are in the trash. It was originally made from a light cream resin, then it was painted

dark blue, and then a rust colored coat was crudely sprayed on at a later date. It is now possible to see all the way to the light cream coat through all the scratches. It is very comfortable, though. It cradles me with its cool plastic skin. The back gives slightly when I lean back. I like this chair. I can carry it around the park with me. I can sit in any combination of shade and sunlight I want so I don’t get too sweaty.

The weather is finally starting to cool off here. The temperature dips below sixty at night and never rises above eighty in the day. Regardless, I will always think of New Orleans whenever I break into a sweat .

-Caleb Sears